Leah Wagner and Nick Schlosstein own Foundroot. (Jillian Rogers)

Farmers Leah Wagner and Nick Schlosstein have planted roots in Haines to embark a unique business venture. Foundroot focuses mostly on seed cultivation, sustainable farming, and permaculture.

For non-gardeners, February is perhaps just another snowy, winter month. But for those who farm, big or small, February means seed-mania. A lot of thought goes into what to plant and where to plant it, especially in Alaska, where the growing season is short and difficult. For Wagner and Schlosstein, getting into the seed biz has been a few years in the making.

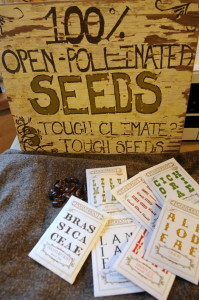

“Foundroot started as an open-pollinated vegetable seed company and we’re sort of expanding into bigger ideas from there,” says Wagner. “We grow permaculturally, we talk a lot about sustainable homesteading methods, a lot of traditional wildcrafting and just ways to live in a more sustainable way specifically in Alaska and other cold-climate places.”

(Jillian Rogers)

She says she learned the art of seed saving in the Lower 48 and British Columbia. Then she moved to Palmer and worked for an organic farm there. She says, she noticed something right away.

“There was just such a need for more food and it didn’t matter how much anyone produced, there was this huge demand for better, local food everywhere. We couldn’t hold onto any of vegetables any week at market and it seemed like that was the same situation for any of the farmers in the area.”

The funny thing about that, Wagner says, is that no one was really discussing seeds. Seed saving allows for more abundant and better varieties of vegetables.

After her first summer in Alaska, Wagner went to “seed school” in Arizona. So, what does a seed course in the desert have to do farming in Alaska? Wagner says the instructor was well-versed in growing in cold climates and high altitudes, as well as nurturing crops through drought.

“Seed school was essentially a crash course in all things seeds. We talked about issues with GMOs (genetically modified organism) and political power and the companies that own our seeds right now and loss of diversity.”

Foundroot has been selling non-GMO seeds from outside the state – a wide variety of hearty veggies, that do well in Alaska, grown and harvested ethically. Wagner says most of the seeds they sell are heirloom seeds, or varieties that have a long history. This is Foundroot’s fourth year in operation, and they sell seeds, mostly online, to farmers across the state, as far north as Anaktuvuk Pass.

“Southeast is really a new market for us and we feel like the seeds will be really viable here,” Wagner says. “And so it’s really exciting to be in this area and let folks know what we’re doing because we already have a lot of support in other areas.”

Schlosstein says there has been a huge loss in variety over the decades with more and more large-scale farming.

“Now you go to the store and all carrots are orange,” he says. “And that’s not anything to do with the properties of a carrot, that’s just a more marketable thing.”

(Jillian Rogers)

Wagner adds: “We have round, red carrots and we have long, white beets, but no one sees those in the same way. There is a resurgence of that now, there is a huge movement to bring those heirloom seeds back and those really rare varieties.”

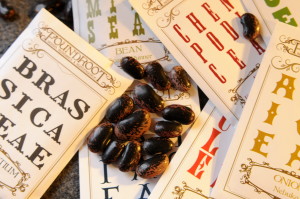

The process of producing seeds for sale means they’ll have a robust garden on their small plot of land eventually, but a lot of seeds are best harvested long after the vegetables are prime for picking.

Schlosstein and Wagner say keeping the plants alive, some still in the ground, over winter so they can then collect the seeds will be a challenge. Produce like tomatoes or peppers, you can just pluck the seeds out before you eat the meat. Carrots have to go through a winter in the ground before producing flowers the next spring. Once the veggie has flowered, the seeds are eligible to be snatched, sold and planted. Many varieties, though, will produce seeds within one Alaska growing season.

“Usually with seeds, you want them to be on the plant, in the ground, as long as possible to get all that great information and all that energy into the seed,” says Wagner.

Wagner says if you’re a seasoned farmer, saving seeds is intuitive and easy. And there have been seed savers in the state for years ‑ a farmer in Homer, and one near Fairbanks, but it’s not exactly a popular pastime.

“So, for us, we really hope to be a full circle operation and this is going to be our first year transitioning into growing and selling Alaska-grown seeds,” says Wagner.

The green-thumbed pair is just starting out in Haines. They live in a small yurt and currently only have about a half-acre cleared for their garden. Wagner says they’re hoping to produce enough vegetables to be eligible for a federal high-tunnel grant program, which would provide them more indoor growing space. For now, the plan is to make several small hoop houses and plant as much as they can outside. The transition from selling Outside seeds, to selling all Alaska-grown seeds will take a while, they say.

Launching into the Alaska-grown seed market is exciting, they say. And they’re hoping to start selling their first batches of homegrown seeds in 2017. Besides offering food ownership and security, they want to make gardening simple for new farmers by offering tough, tasty, Alaska-worthy varieties.

I’m looking forward to meeting you both. I got excited when I read the article. I still live in S. CA, but am transitioning to Haines as these words go into text! AK permaculture is of interest to me. I know nothing, but keep getting drawn to the topic of sustainable homesteading in Haines. We’ll see where my dreams lead.