(Credit: Alaska Department of Fish and Game)

State biologists now have a clearer picture of how mining impacts mountain goats. The first-ever Alaska-based study on mining and mountain goat habitat was published recently. It tracked the movements of goats in the area around Kensington Mine, a gold mine between Haines and Juneau, near Berners Bay.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game study confirmed what biologists already suspected: mining impacts mountain goat habitat selection.

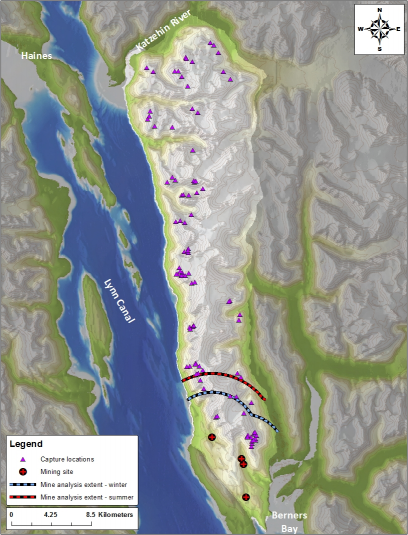

Map depicting the geographical extent of the study area. The light blue and red lines delineate the winter and summer extents used in the mine proximity analyses. The purple triangles indicate the mountain goat capture locations, and the red crosses depict mine activity sites. (ADF&G)

The study’s inception coincided with the start of Kensington mine’s development in 2005. Biologists mapped where mountain goats live in Kakuhan Range. They captured and put GPS radio collars on 75 animals, 18 of which were collared near the mining area. Biologist Kevin White led the research.

“Within this area, the types of activities that are occurring involve blasting, helicopter activity, heavy equipment operation and vehicle traffic,” White explained.

The question was, how much would that activity affect mountain goat habitat selection? In other words, would mountain goats avoid areas close to the mine?

At a presentation at the Takshanuk Watershed Council office last week, White showed a map that included Lion’s Head Mountain, where some of the goats spend summers. The mountain is bordered on the east and west by what his team identified as critical winter habitat, which is at lower elevations.

“Those animals are summering up on that ridge, and in the winter they have a decision,” White said. “Are they going to go down into the bowl where’s there’s critical habitat that’s close to the mine? Or are they going to go down to the other side of the ridge where there’s area far away from the mine?”

Overwhelmingly, the goats veered away from the mining activity. Most chose to winter east, near Berners River, instead of west, toward Johnson Creek.

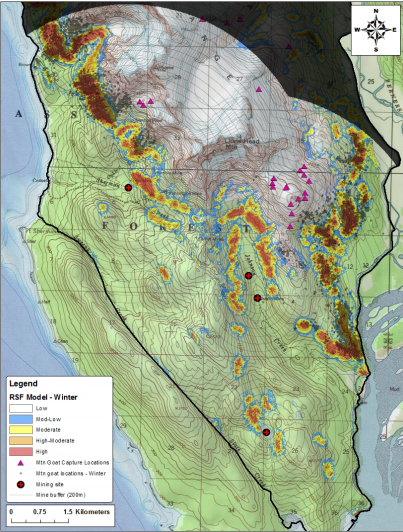

“It’s pretty striking, just looking at this map, you can see there’s virtually no locations in these critical habitat areas that are within 1800 meters of the mine. They’re simply avoiding using that area.”

White says the animals stay away from areas within 1800 meters from the mine. That’s equal to 1.8 kilometers and 1.1 miles. How does that one-mile threshold impact how much habitat the mountain goats have left to choose from? White says, it takes away 42 percent of the winter habitat.

Map depicting mountain goat use of predicted winter habitat in the vicinity of the Kensington Mine. Winter mountain goat GPS locations (grey dots) and capture sites (purple triangles) are plotted along with mine activity centers (red crosses). (ADF&G)

“So essentially that’s habitat functionally being taken away from the mountain goats,” White said. “So there’s been a roughly a 42 percent decline in winter habitat as a function of the mine.”

“It’s not earth-shattering,” said Ryan Scott, Fish and Game’s Wildlife Conservation regional supervisor “Intuitively it makes sense that when you have some kind of disturbance, whether it’s mining or other things, that mountain goats are going to avoid certain areas,” Scott said. “And we’re seeing that.”

What are the implications of these findings? White says, the first is obvious. Mining activity should not occur within one mile of mountain goat winter habitat. But in some cases, like the Kensington Mine, it’s too late.

White says when winter habitat is reduced, mountain goat populations’ productivity and resilience could be damaged. Fish and Game will continue to monitor the animals to see if there are detrimental changes to the population.

“Goats are a tough one,” Scott said. “They live in a tough spot, they’re slow to reproduce, they don’t handle disturbance too well. But there are things we can do to help them out, to try to minimize the amount of impact.”

Scott says there has not yet been a conversation about whether there’s anything to be done about the disturbances around Kensington.

As for the mineral exploration that’s happening near Haines, Scott says this study will influence the recommendations he makes. Constantine Metal Resources recently filed a proposed plan to expand operations at the Palmer Project, where the company is exploring for gold, silver, copper and zinc. An environmental assessment of the plan from the Bureau of Land Management is out for public comment. Scott says Fish and Game will file a comment related to mountain goat habitat protection.

Overall, the biologists say the discovery of the one-mile buffer zone is really important. It will help inform how Fish and Game looks at future mining decision in mountain goat land.

Related: Biologist tracks Chilkat Valley mountain goats to map habitat