Andrea Nelson spent 14 days on the Chilkoot Trail recently as part of an artist residency program. (Jillian Rogers)

Haines artist Andrea Nelson returned home earlier this month from a two-week trek over the Chilkoot Trail. Most backpackers are limited to a handful of days on the rustic route, but Nelson’s quest was different. She was one of three creative minds selected for the Chilkoot Artist in Residence program.

Every day is a treasure hunt for Nelson. She’s always keeping a watchful eye on her surroundings, not just for objects to add to her collage sculptures – or assemblages – but for colors, designs, and patterns. But because her 14-day residency took place on a national historic site, she couldn’t, and wouldn’t want to, pocket any found items.

“It wasn’t so much about accumulating objects as observing just that phenomenon of human remnants,” she says.

Nelson was chosen for the Chilkoot residency, a joint effort through the National Park Service, Parks Canada, the Yukon Arts Center, the Skagway Arts Council and Alaska Geographic. Three visual artists are selected for the trip over the 33-mile trail – one American, one Canadian, and one regional artist from either Alaska or the Yukon. That was Nelson. The trail saw thousands of gold-seekers battle the rugged terrain in the late 1800s during the Klondike Gold Rush. Hints of the bygone era still litter the path. But nature is taking its course.

“Places that once had thousands of people, now have nothing. I mean, the forest has just swallowed it.”

(Sandi Coleman/CBC)

She says seeing things like wolf tracks mingling amongst old, rusted cans, or fungi and lichen creeping into, and onto, corroded pieces of machinery that were abandoned over a century ago, was fascinating.

“One of things that really caught my eye on this trail were the Victorian details, like ornamental details, on some of the remnants. They were so unexpected because everything is so utilitarian and rugged.”

The residency program is in its sixth year. Nelson says it aims to inspire artists for a project, or projects, that capture their own interpretation of life, past and present, on the trail.

“As well as starting art along the trail, and interacting with other hikers to enrich their experience of seeing the area through a different lens.”

Along the way, Nelson hiked and camped, but because the residency lasted 14 days, she was able to really stop and spend time at interesting areas along the historic route. Permitted hikers are herded up and over in a limited amount time, so Nelson says being able to pause, take in her surroundings, and interact with people on the trail, was a unique experience. For the most part, despite lots of rain and a 70-pound pack loaded with camping and art supplies, she maintained an easy pace.

“With one big day in the middle, that goes over the pass,” she says. (The trail) “traverses through multiple ecosystems and vegetation types and geology as you go alone. And of course, the remains of tens of thousands of people who went before us; stampeders, and the Native traders hundreds of years before that.”

During the first few days, because of the rain and water-logged trail, and a heavy pack that her body was still adjusting to, Nelson says she put being an artist on the back-burner and just tried to survive. But she says, those early days gave her an idea of the power of the trail. She says she could feel the struggle of those who made the trek so many decades ago.

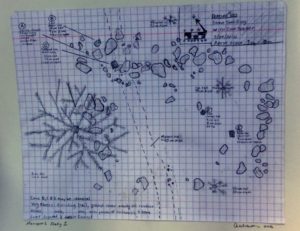

Once she got into her groove, though, she would stop to take notes, draw maps, take photographs, and really try to absorb her surroundings.

“I knew that I wanted to collapse my background in archaeological work, and museum work, into my art. I wanted to look at the Chilkoot Trail as a larger cultural and natural landscape.”

Just how this approach would manifest itself into final art pieces wasn’t clear when Nelson started at the Dyea trailhead in mid-July. She’s currently in the process of sorting through all the notes, and diagrams, and photos she collected on the journey to come up with what she calls a mock archaeological documentation. Nelson says she’ll also try to recreate some of the relics she saw on the trail with items she already has.

“So, I’ve mapped a lot, diagramed, took a lot of notes on human behavior, and just … kind of mixing some different approaches. And then I’ll be using some of my own collections to make a conglomeration.”

And her project won’t just focus on the historical significance of the route, but the modern Chilkoot Trail scene, too.

“I paid a lot of attention to hiker behavior from camp to camp, and how that correlates to probable stampeder attitudes,” she says. “For example, the camp right before the pass is where people get very anxious and fidgety, and they leave things behind, on accident or on purpose, because they don’t want to carry them. I imagine the stampeders with the same attitude, as well as a great deal of relief at the next camp.”

She says she even documented trash left behind by modern day hikers – hiking-pole tips, wrappers, and Band-Aids. She says she likes the parallel between the old and new.

Nelson says the timeline for the finished project is lenient. She’ll be working on it over the winter and she hopes to present it in Haines, Skagway, Whitehorse, and possibly Dawson City, sometime next year.