Alaska Fish and Game is stepping up its research in Southeast on a certain nocturnal, bug-eating animal. Bats in the lower 48 are being threatened by a disease called White-Nose Syndrome. That’s prompting Alaska researchers to find out which bats live here and where they roost. But they can’t do all the work by themselves, so they’re enlisting the public’s help.

The sun has just set, and Pam Randles is driving her car 20 miles per hour along the Chilkoot River. A quick tapping sound comes through a bat monitor.

“That’s bats!” Randles says. “You drive along very slowly and you keep a steady pace and all of a sudden chitter, chitter, chitter and it’s like whoa! It worked! You really can hear them!”

The human ear can’t hear bat sounds. So Randles’ car has been turned into a batmobile. There’s an ultrasonic microphone attached to the top of the car, and a little box inside that plays and records the bat calls the microphone picks up. A GPS pinpoints the location of the sounds.

“I mean it’s a huge project. We couldn’t do it without citizen scientists,” said Michael Kohan, a biologist with Fish and Game and one of the researchers on the bat study.

Their work started in 2011. But last year, they ramped up their efforts by getting citizen scientists involved in acoustic driving surveys.

“Anybody can go out and record bat calls,” Kohan said. “We have a certain route where we’re interested in seeing what bat species are on that route and where are they are. And people will go out and record bat calls as they drive.”

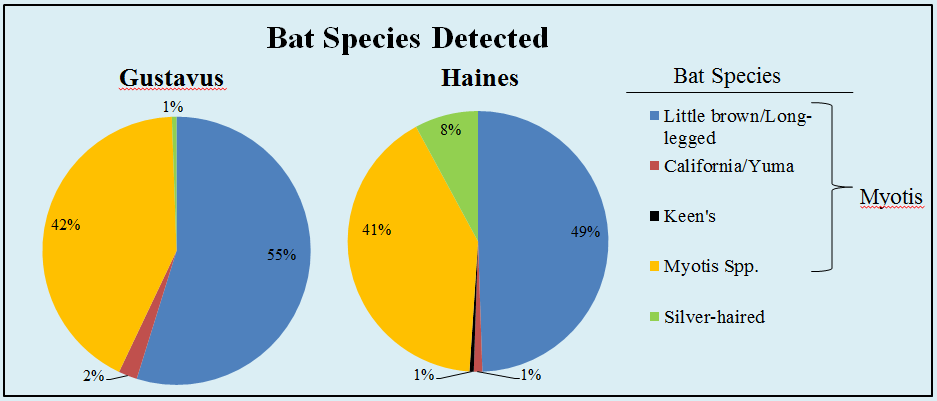

Kohan says last summer the surveys were hugely successful in the first two communities — Haines and Gustavus. 30 volunteers participated. This summer, Kohan is expanding the program to Juneau, Craig, Petersburg, Wrangell and Sitka. In Haines, the library has a sign-up sheet for the bat detectors. People can check them out for two weeks at a time.

But when the people collecting data are not scientists, can you trust them?

“The way that our research project is orientated is we’re asking specific information from citizen scientists that provides no room for failure,” Kohan said.

Randles puts it a different way. She says the design is “idiot-proof.”

The citizen scientist just puts the microphone on their car, turns on the bat call detector, and fills out a sheet of paper with the information like the time and weather conditions. Fish and Game then takes the driving survey data to figure out where bats roost and what species they are.

Kohan saysthey’ve found four species of bats in Haines and Gustavus. They include the silver-haired bats, little brown bats and California bats. Getting a sense of the bat population here gives scientists a baseline in case the disease White-Nose Syndrome spreads to Alaska.

“When you see a bat that’s affected by White-Nose Syndrome, the white fungal disease is actually on their nose. It’s a white fuzzy mold basically that’s growing on their nose and wings,” Kohan said.

Since 2006, scientists estimate 80 percent of the bat population in the northeastern US died from White-Nose Syndrome.

“It is a threat to bats right now, a big threat to bats. And so scientists as a whole are trying to come up with a way to monitor the population of bats on a North America-wide effort. And so that’s why these driving surveys and the stationary detectors are useful. We can use the information and send it to this huge database to be able to monitor bat populations.”

So, bat scientists are clearly concerned about bats. But how do you make the average person care about them?

“I try to incorporate the importance of bats in the way that bats can eat mosquitoes,” Kohan said. “So they’re voracious mosquito eaters. A single little brown bat which is the size of your thumb can eat 1,000 mosquitoes in an hour.”

Apparently that pitch has worked. The success of this citizen science project is prompting Fish and Game to expand public involvement. Next summer, they’re hoping to use citizen scientists in amphibian research.

Back in the bat mobile with Randles, it’s been a fairly quiet night. We’ve heard about five bat calls between Chilkoot Lake and end of Mud Bay Road. Randles says her perspective on the little screechy creatures has dramatically changed with the help of this project.

“I hated bats,” Randles said. “Because long ago and far away when I was a teenager, I was out on a beach with, at that moment, the love of my life, and these bats kept dive-bombing us and it just freaked me out. I got completely scared of them and was scared for 45 years. Then when I come out here to study these guys, all of a sudden I’m not hating bats for no reason. I have a better appreciation for them.”

For more information on bats and citizen science in Alaska, please visit the ADFG website at: www.citizenscience.adfg.alaska.gov